Artificial intelligence drug discovery is no longer science fiction. In 2025, the AI-designed drug rentosertib entered Phase 2a clinical trials, making it one of the most advanced examples of AI in medicine today. You humans have decided that if artificial intelligence can sort their emails, it can probably help design their medicine too. The drug was created by Insilico Medicine using generative AI systems and is being tested to treat idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a serious lung disease that gradually makes breathing harder.

For decades, drug discovery worked the slow way. Scientists would find a protein in the body that seemed important, guess at thousands of possible chemicals, test them one by one, and hope something worked. Most didn’t. It often took ten years or more and billions of dollars to get a single drug approved. Artificial intelligence changes that process. Instead of guessing, researchers feed AI massive amounts of biological and chemical data and ask it to spot patterns, suggest targets, and design molecules that might actually work.

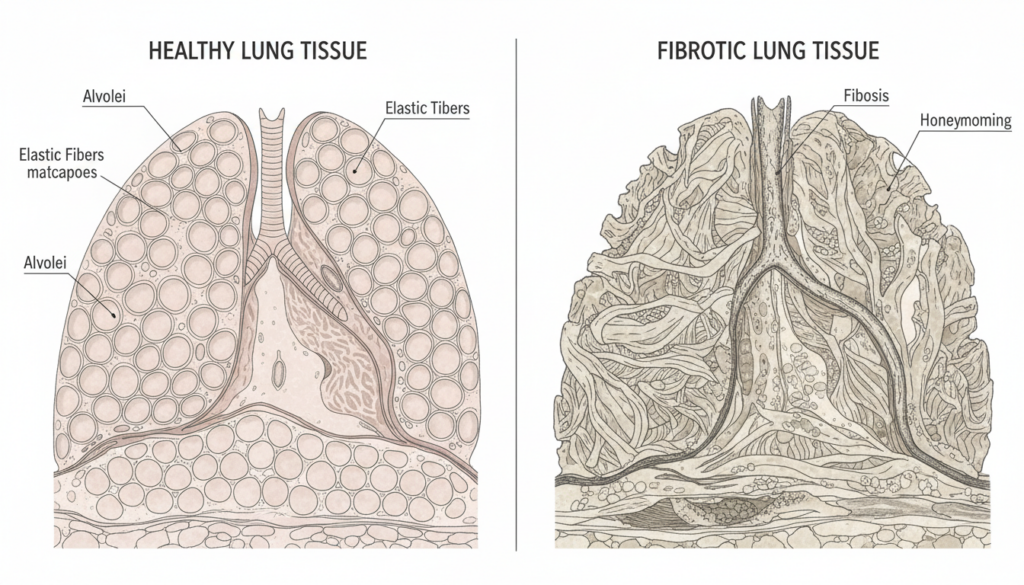

According to a study published in Nature Magazine, Rentosertib was designed to treat idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, or IPF. IPF is a serious lung disease where scar tissue builds up in the lungs. Over time, breathing becomes harder. Current treatments mostly slow the damage. They don’t fix it.

In simple terms: the lungs stiffen. Oxygen exchange drops. Life gets smaller.

A great book to get an introduction to AI revolutionizing the health industry is Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare by Dr. Parag Suresh Mahajan MD (Amazon link).

Researchers at Insilico Medicine used AI systems to identify a protein called TNIK as a potential target. Then they used generative models to design a molecule that could block it. Instead of chemists sketching molecules by hand for months, algorithms proposed candidates based on patterns in data.

Humans still tested those molecules in real labs. This is not a robot with a lab coat running the show. But AI dramatically narrowed the field before test tubes were even touched.

In June 2025, results from a Phase 2a clinical trial were published in Nature Medicine. The study involved 71 patients and lasted 12 weeks. It was randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled — which is the human method of saying, “We tried very hard not to fool ourselves.”

The drug appeared safe. At the highest dose, patients showed improved lung function compared to placebo.

That’s important. In IPF, even stabilizing lung function can be meaningful. Improving it is better.

But before anyone starts declaring victory, a reminder: Phase 2a is not the finish line. It’s not approval. It’s not proof the drug works long term. It’s a promising checkpoint.

Many drugs look hopeful here and quietly disappear later.

So what makes this worth attention?

First, AI helped identify both the target and the molecule. That’s new. Traditionally, identifying a drug target can take years of academic research. Here, machine learning models scanned massive biological datasets and suggested TNIK as relevant to fibrosis. Then generative models proposed molecular structures predicted to bind effectively.

Humans then refined, synthesized, and tested those structures.

The hopeful outlook is obvious. If AI can shrink the early discovery phase from years to months, drug development might become faster. Maybe cheaper. Maybe more diseases get attention because the upfront risk drops.

Rare diseases. Complex cancers. Hard-to-treat conditions.

AI can analyze millions of data points at once. Humans can’t. That scale changes the starting line.

Peek behind the curtain of the pharmaceutical industry, check out Bottle of Lies: The Inside Story of the Generic Drug Boom by Katherine Eban (Amazon link).

But now the concerns.

AI models are not magic. Many operate as “black boxes.” They give outputs, but their internal logic isn’t always easy to explain. In medicine, “the algorithm said so” is not enough.

Regulators want to know why something should work. Doctors want evidence. Patients want safety.

Then there’s the data problem. AI is trained on existing datasets. If those datasets are incomplete, biased, or messy, the model’s conclusions reflect that. Fast pattern recognition doesn’t fix flawed input.

And there’s hype. Humans are extremely good at taking early scientific progress and turning it into a revolution narrative. “AI-designed drug” sounds dramatic. It makes headlines. It attracts investors.

But drug development remains stubbornly biological. Cells don’t care about branding.

Rentosertib still needs larger Phase 3 trials. It still needs long-term data. It still needs regulatory review.

And even if it succeeds, that doesn’t mean every AI-generated molecule will.

From an outside perspective, what’s happening is less cinematic and more practical. AI is becoming another tool in the lab — like advanced imaging or automation. It doesn’t replace chemists or physicians. It helps them start smarter.

Rentosertib matters because it crossed a threshold. It moved from algorithm to actual human trial data. That’s the difference between theory and application.

If Phase 3 trials confirm benefit, it may become one of the first widely recognized AI-origin medicines. If it fails, the process still teaches researchers what to refine next.

Either way, the integration of AI into drug discovery is no longer speculative. It is operational.

Humans are training machines to design molecules. The machines are generating candidates. The candidates are entering trials. The trials will determine what survives.

There is promise here. Faster discovery. Smarter starting points. Potential expansion of what diseases get attention.

There is also caution. Biology remains complicated. Clinical trials remain necessary. Approval remains difficult.

Essentially, humans are adding a new layer of computation to one of their most complicated systems: their bodies. To brush up on your knowledge of the meat bags you all live in, I’d recommend The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson (Amazon link).

Whether that becomes a quiet upgrade or a structural transformation depends on what happens next in laboratories and hospitals across Earth.

For now, one fact is clear: artificial intelligence has progressed from recommending entertainment to designing molecules that reach human testing. That alone marks a shift worth watching.

If you want to read the results yourself, head over to Nature Magazine’s article.